silences

solo exhibition

2005

Belger Art Center

Kansas City, Missouri

components of this exhibition were also exhibited in Decelerate at the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art

Kansas City, Missouri, 2006

curated by Elizabeth Dunbar

excerpt from exhibition essay by Elizabeth Dunbar

essay for silences by Dan Siedell, Curator, Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery and Sculpture Garden, University of Nebraska

"Ours is an ugly, shrill, and loud culture. And it is getting worse by the moment. The result is polarized, balkanized, isolated communities using language as a weapon of separation rather than for mutual understanding. It is this cultural landscape that gives Anne Lindberg’s silences an urgent, activist undertone. To our noisy, polemical culture, silence appears to be a sign of weakness or at the very least, a cause for suspicion. But it is in reality a source of profound strength in both the private and public realm. Any humanizing form of social interaction and communication must take the practice and veneration of silence as its foundation. What our crude and uncivilized culture needs desperately is thus not more discourse, but better discourse. silences is Lindberg’s aesthetic meditation on what better discourse might look and feel like.

silences consists of four separate but connected works, each of which functions as a visual metaphor for a “stage” or “level” in the development of the human person as a social being. One does not, however, proceed from one level to the next; all four of these levels coexist, mingle, and inform the other, in a dynamic between biology and culture.

The first work, which cuts the exhibition space into two parts, serving as the “id” of the installation, is appropriately titled old brain. It is the most purely visually magnificent work in the installation. It consists of a twenty six-foot long pile of silver thread that weighs over 650 lbs and is laid directly on the floor. The sheer mass of the work as an object gives way upon closer examination to an elegant and graceful layering of various shades of material as it weaves the object. It is not surprising, then, that Lindberg conceives of this piece as a visual, experiential metaphor for raw emotion and energy.

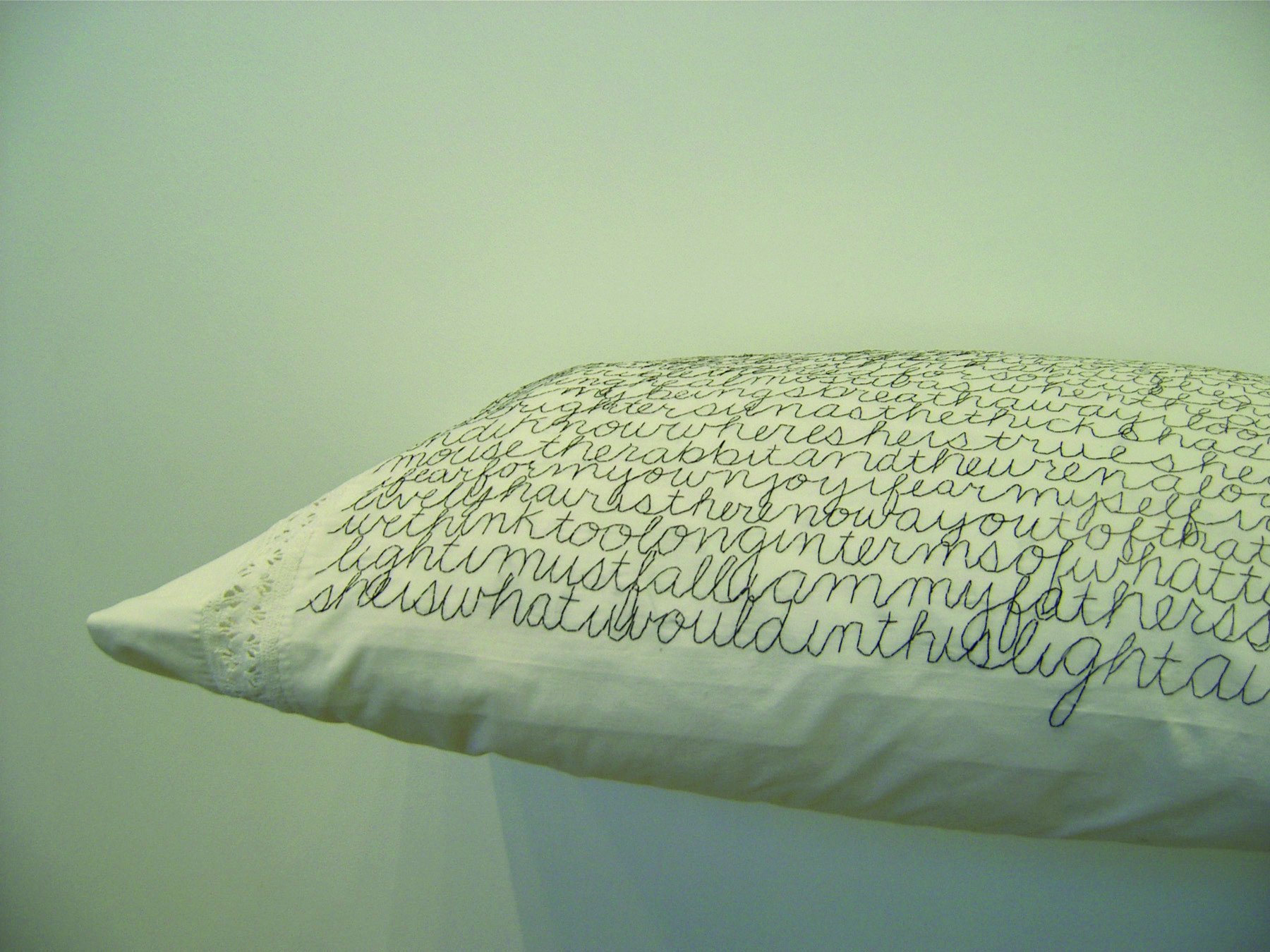

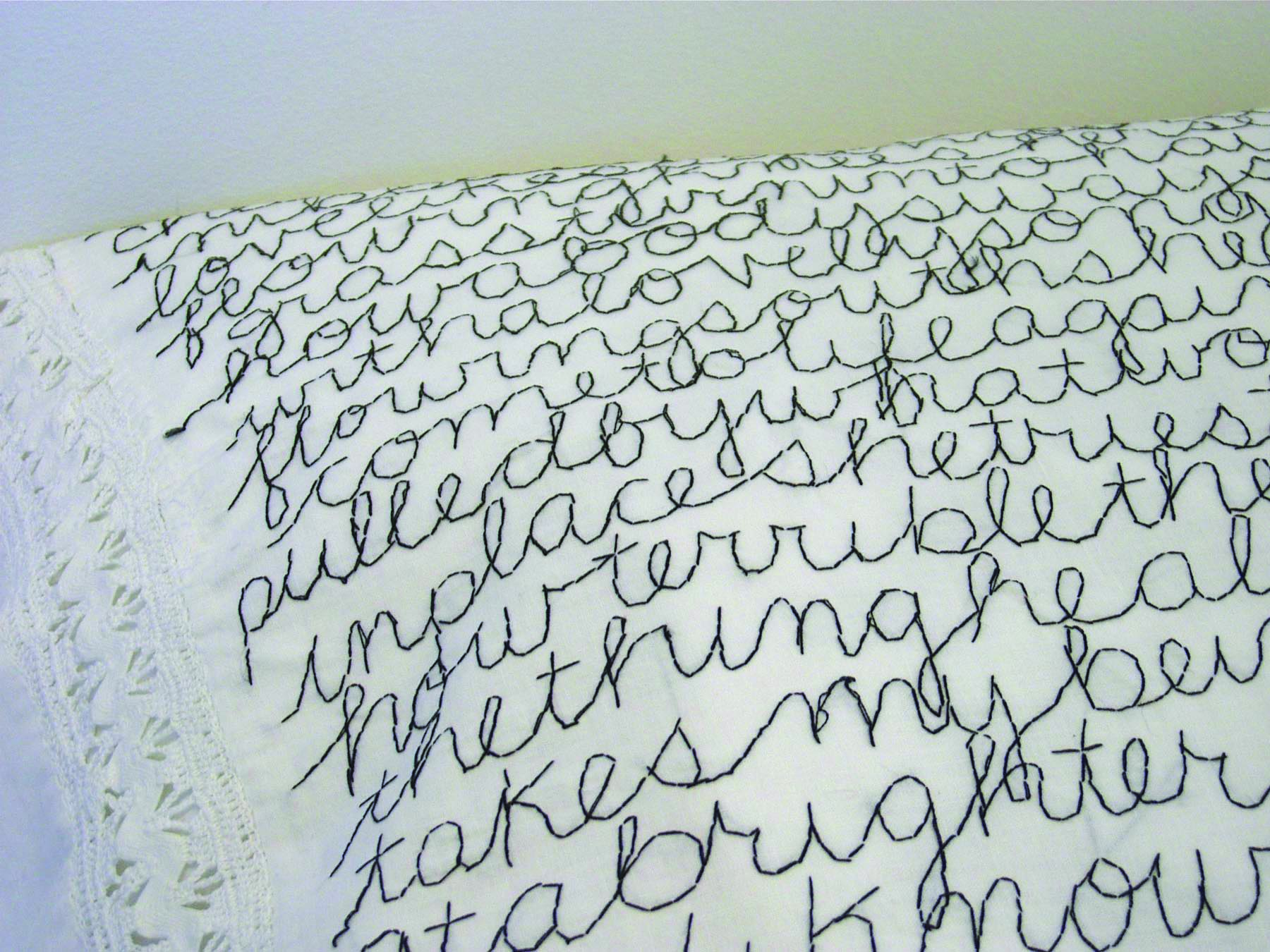

The second work is entitled sleep and it consists of two pillows, one made out of the length of a bed sheet, installed on a wall. Lindberg has stitched on these handmade pillows in script fragments from the poetry of Theodore Roethke. These largely illegible fragments pool in circular “language clusters” that mark a human presence. This is where language is subconscious, where, unhinged to “reason” and the practicalities of everyday usage, language takes on a life of its own in the privacy and secrecy of one’s psyche.

Next to behold is an installation that consists of sixteen drawers, scavenged by Lindberg and mounted on the wall, each packed tightly with various colored thread. Entitled behold, this work suggests a transitional space, one between the public and private, in which thread, carrying the metaphor of the visceral, pre-linguistic experience is “contained” in an ambiguously social or only semi-social place. Although they are opened drawers accessible to us to peer into, they still remain private space.

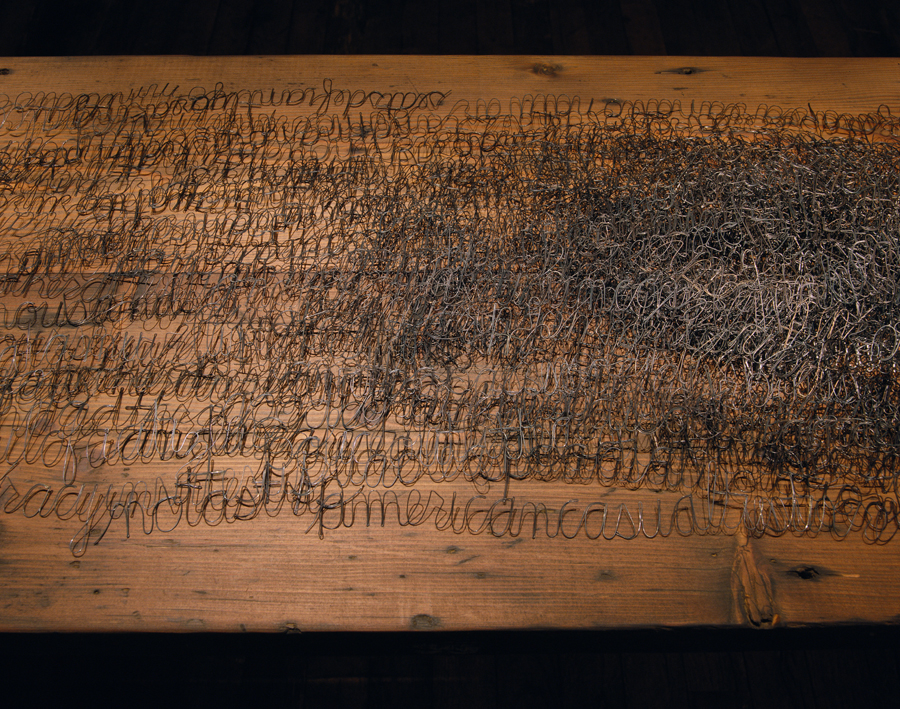

democracy is the climax of silences. It is also the most personal. It consists of a harvest table that she has crafted, on which is placed a nearly complete transcription, in cut wire, of writer Terry Tempest Williams’s controversial essay “Commencement,” in The Open Space of Democracy (2004), which bemoans the shrinking space for dialogue in cultural life. This is the most public and thoroughly socialized of Lindberg’s metaphorical spaces, a space of social interaction: the dinner table, a place in which a family and guests embody hospitality through sharing conversation and food. It is also a place where the social sphere is rehearsed on a daily basis, where the conversation plays a role almost as important as taking in the meal itself. It is not insignificant that Lindberg has powerful memories of her own family dinner table, which modeled the kind of democratic space that is so rare in American society. Furthermore, this space must be carved out first in the home, carved out among family, friends, and the invited guests, before it can extend to the broader and more abstract reaches of society.

As has been the case with her previous work, physical presence is an important part of silences. First, the sheer physical presence, in mass of corporality, is suggested in old brain; sleeping bodies in sleep; dressing and organizing bodies in behold; and finally, dining and fellowship bodies in democracy. But it also suggests the physical presence of the artist, the laborious process of making, stitching, sewing, carving, and writing. Roethke’s and Williams’s texts are not merely “included” in the installation, Lindberg has “digested” or “consumed” them as they have been transcribed by hand and then stitched or cut. This labor-intensive work, as it has for monks in various religious traditions, becomes a spiritual discipline. And when one is engaged in such doing, silence naturally follows. Contrary to our children’s rhyme, words do hurt us, they hurt each other, our communities, our environment. And they can prevent action as much as they can facilitate it.

silences is an environment in which communication, be it through words or objects, builds up, rather than tears down; unifies rather than divides. Perhaps the very presence, the very beauty of this installation testifies to its very possibility."